Alfred Hitchcock's Lifeboat is an unusual film for the director in many ways. As opposed to his usual freewheeling thrillers, with locales stretching across the world, the action here is confined to the titular lifeboat after a US freighter is sunk by a German U-boat during World War II. The lifeboat gets filled up with rescued passengers from the freighter, and then they take on one last unexpected survivor: the captain of the German U-boat who sank them. The confined locale gives the film a bit of a stagy, theatrical feel to it, and the fact that Hitchcock is able to turn a bunch of talking heads on a boat into a taut, compelling entertainment is tribute enough to his genius for suspense. Which is not to say that it's a totally successful effort, because it isn't. Part of that problem has to lie with the script, which was adapted from a story by John Steinbeck. Its assortment of characters — a communist laborer, a factory owner, an upper-class journalist, a black porter, a nurse, a navy grunt — is too contrived, too much a cross-section of society. And its wartime propaganda sits a bit heavily at times, especially in the ending, which seems rather confused in its message. Either the script, or Hitchcock himself, seems unsure of whether or not the film should be wholeheartedly embracing the characters' blanket condemnation of Germans. There's a strange distanced vibe to the violent outburst at the film's complex (I won't ruin it for you), in which Hitchcock seems to have stepped back from the action in order to keep things objective. He also films it from behind, so that the violence itself isn't seen, and the camera appears to be questioning the validity of what it shows. The ending, unfortunately, erases a lot of this ambiguity, fully endorsing a patriotic message without the earlier shadings of moral ambiguity that had bubbled up periodically throughout the film.

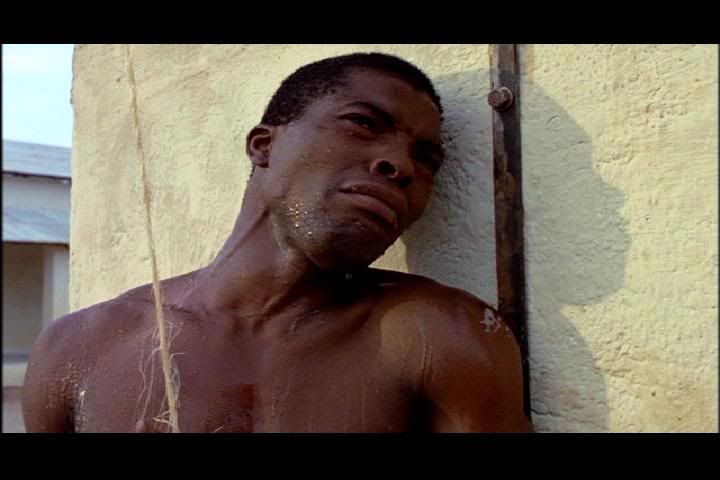

It's as though, somewhere within this, a much more interesting film about patriotism, wartime violence, class, and race were struggling to get out, but the era and the actual real-life war prevented any such nuanced look at the issues. As a result, the film's tokenist look at race is patronizing and falls neatly into place with contemporary stereotypes — something for which Steinbeck himself was reportedly enraged at Hitchcock. The character of the porter, Joe (Canada Lee), is yet another example of the Hollywood "magical Negro" figure, with the recorder he plays and his background in pickpocketing and his willingness to continue playing the servant even in extraordinary circumstances. He's unsurprisingly also the film's voice of religion, and is given a scene in which he intones a hymnal for the burial at sea of a drowned baby. It's one of the film's most striking images, with high-contrast lighting producing textured silhouettes, but it also completes the picture of Joe as a quasi-mystical figure, which makes it much easier to forget him slaving away in the background for the rest of the film.

The depiction of class is equally superficial, a paper-thin contrast between angry Communist worker Kovac (John Hodiak) and the glamorous reporter Connie (Tallulah Bankhead, in a performance of sultry majesty). Here, the blame can't be laid on Hitchcock, but presumably on the original story. Steinbeck was a socialist himself, and it's clear that he saw the dialogues between Kovac and Connie (and, to a lesser extent, the factory boss played by Henry Hull) as a perfect opportunity to reveal class tensions. But it's equally clear that the script looks at these tensions in only the most basic ways, and the dialogue along these lines never gets much further than a Marxist primer, with no subtlety or true exchange of ideas. Still, the film isn't a total flop by any means. Bankhead, as already mentioned, turns in a wonder of a performance, stealing scenes left and right with her laidback sensuality, and the rest of the cast holds up admirably with the sometimes clunky script. And the suspense is sustained beautifully, of course, even if the supposed mystery — the German captain's intentions — is never really a subject of much doubt from the audience's POV. Ultimately, this is a decent if uncharacteristic Hitchcock thriller, somewhat bogged down by thematic issues.

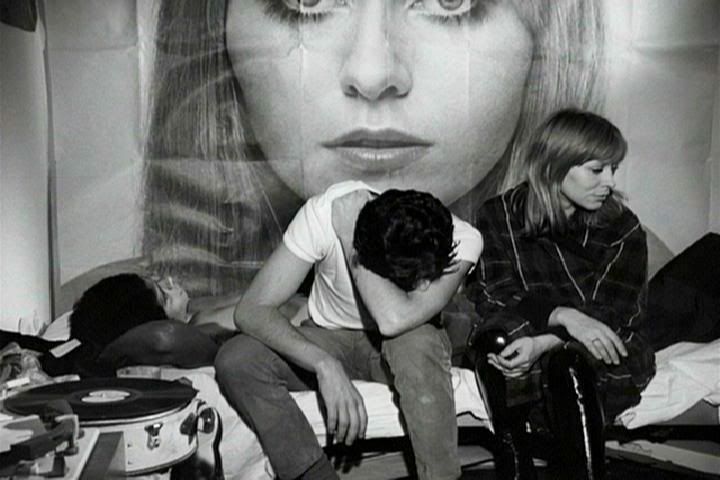

Fellini's Amarcord is a late masterpiece from this director who excelled at translating the figments of his imagination onto the screen. Nowhere is that more apparent than here, in which the entire film is a loosely connected series of vignettes presenting an extremely exaggerated, phantasmagoric image of Fellini's memories of his childhood home town of Rimini. This is in many ways a continuation of the kind of circus atmosphere that proliferated throughout 8 1/2, except in that case the circus revolved around one central figure, the frustrated director played by Marcello Mastroianni. Here, there is no such central character; the town itself is the main character. The story, such as it is, is just the passing of a year in the town's life, following the change of the season and relating anecdotes about many of the residents. The film both opens and closes with the swirling of the "lemone," the yellow wisps which for this town signal the end of winter and the onset of spring. In between, all sorts of things happen, and things change, but there's not a real sense of narrative; it's all just part of the fabric of the town's life. This impression is heightened by the presence of a running commentary on the town's ancient history by a lawyer and local historian, who speaks directly to the camera from within scenes. Other characters periodically address the camera, too, giving the impression that there is some kind of journalistic documenter surveying the town — Fellini himself, maybe.

But this documentary facade does nothing to improve the film's sense of reality. Quite to the contrary, these acknowledgments of the camera serve much the same purpose that they do in early Godard, to disconnect the film from reality. Not that that disconnection isn't apparent everywhere in Fellini's work here. Even more so than in any of his earlier films, everything here is subsumed by the swirling circus atmosphere, with Nino Rota's bouncy score driving along scenes of chaotic celebration and angry arguments alike. Even a ritualistic fascist rally, complete with a giant Mussolini head made of flowers, is filmed with the same over-the-top energy and vitality, demonstrating how easily the townspeople's vibrant personalities could be absorbed by the Mussolini machine. The fascists provide an ugly underbelly to the film as a whole, especially in a chillingly underplayed scene in which they force a local socialist-sympathizer to drink castor oil, a common punishment doled out by Italian fascists. Their malevolent presence in the town is an occasional chill wind through the otherwise pristine village of Fellini's reminiscences.

In many ways, this is a true Fellini primer. All of his obsessions are on display here, exaggerated to mammoth proportions. There's Volpina, the ridiculously over-acted local tramp who seems to exude animal sexuality from her every moment. Her leering and fidgety movements go well with clothes that somehow seem like they're in danger of simply peeling away from her body at any moment. This is Fellini's image of sex, which always has a healthy dose of the perverse to it, of the crazy even. The lunacy is accentuated by the character of Teo, a mildly retarded man who one day snaps, climbs to the top of a tree, and begins screaming out "I want a woman" across the fields. He's only brought down — of course, since this is Fellini — by the arrival of a midget nun. There's also the wonderfully hilarious scene in which the young boy Titta receives his sexual initiation at the teat of the buxom grocery store woman, who bares her massive breasts (speaking of mammoth proportions...) and orders him to suck. For Fellini, childhood is a garbled mix of sexual obsessions, school pranks, eccentric grown-ups looming large, and the occasional numbing censure of religion or discipline-minded adults. His gift is transforming the hazy, time-distorted memory of these things into a sublime, ecstatic celebration of all the little moments of life, transformed by reminiscence into events of epic importance. His film even contains some wry comments about this process of storytelling, in the character of Biscein, who tells wildly exaggerated tales of seducing Arab concubines and travelling to America. In so many ways, Fellini is Biscein, and it is through the warped lens of his memory and imagination that we can see the life of this town and its amazing people.