I Was a Male War Bride manages to take a madcap premise, a first-rate comic actor, and a director famed for his mastery of screwball comedies, and still produce a boring, turgid mess of a movie with few enough smiles, let alone laughs. It should be comic gold: reunite Cary Grant with director Howard Hawks and give them a plot that pits Grant's stolid masculinity against a gender-bending scenario where he's forced to pose as a "war bride." Unfortunately, the script is as flat and characterless as a blank sheet of paper, and even the best efforts of Grant — a fine physical comedian who's always ready with some priceless facial expressions whenever the dialogue fails to crackle — can't salvage this turkey.

The film's problems start with casting Grant as a French officer in the aftermath of World War II, since he's as American as gas-guzzlers and greasy fast food: one is constantly wondering why there's such a fuss over his supposedly foreign status, when he's speaking English just as well as anybody else. There are even a few jokes that point out the incongruity, when American soldiers begin speaking to Grant in mangled French, while he answers them with his perfect unaccented English. It's obvious that everyone involved knew how ridiculous the whole set-up was, and these sly winks acknowledge that at least they're in on the joke. Grant plays opposite Ann Sheridan, as an American officer who he's placed on assignment with despite their past history of bickering and fighting. He spends the first half of the movie hating her and continually butting heads with her, at least until he decides he wants to marry her: then he spends the second half of the movie frustrated that he can't spend more time alone with her. Sheridan and Grant are both good actors, but there's virtually no comedic or romantic chemistry between them, mainly because the script gives them little chance to develop any; the dialogue has no sizzle, no momentum, and too often Sheridan is reduced to simply laughing while she watches Grant do something kind of goofy. Their sudden romance is thus completely without a foundation, and the switch from standoffish sparring to lovey-dovey canoodling is awkwardly handled. They go from kissing one moment, for the first time, directly to announcing their marriage.

The film does earn some chuckles along the way, mostly from Grant's deadpan handling of the script's understated humor. His grumpy back-and-forth with Sheridan yields some moments of comic interplay, though the spartan dialogue never gives the duo a chance to really let loose in screwball style. They're rarely allowed to simply spar and trade quips for its own sake, as Grant often did in lead turns opposite Jean Arthur or Katharine Hepburn. Not that Sheridan doesn't seem game for it — she's cheery and has a playful attitude that makes her fun to watch — but the dialogue is too practical, too focused on advancing the utterly uninteresting plot, so that the two of them rarely talk to each other except about what's happening at that immediate moment. Grant fares much better with non-verbal humor, and a lot of the film's best moments come from his physical comedy. There's a running gag where Grant, always forced to sleep in unconventional places, struggles to get comfortable, first while sitting in a chair and then jammed up in the fetus position in a bathtub. It wouldn't be funny in itself, but Grant mimes his discomfort and his awkward contortions brilliantly, doing a lot of the work with his big, slab-like hands, which he can never seem to find a good place to rest.

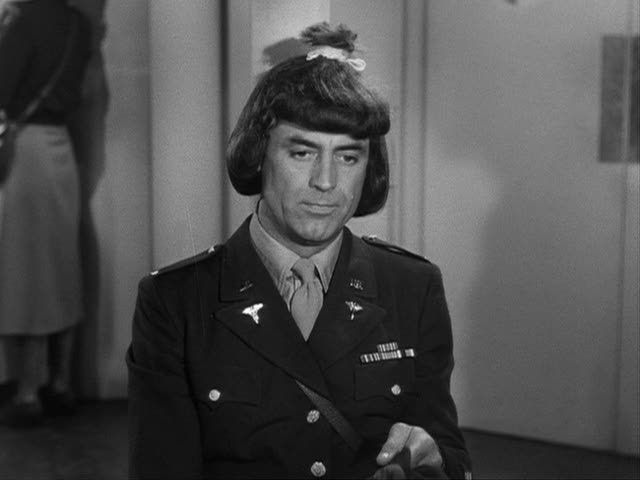

Grant's physicality also injects a lot of humor into the final stretch of the film, when army regulations force him to register himself as a "war bride" in order to be able to enter the United States with his new wife. It's a clever bit of satire, poking fun at both the torturous maze of military regulations and documentation, and an inherently sexist culture where sex roles are so rigidly codified that even the paperwork makes assumptions about what men and women can and can't do. There's some downright subversive material hidden here, about how uncompromising society can be in its accepted situations and behaviors for men or women. Ultimately, it's easier for Grant to simply pose as a woman — with a hideous horsehair wig and that distinctly un-feminine mug of his — than to continue explaining how he came to be a man in the situation he's in.

It's unfortunate that this satire isn't made the focus of the film, since it's definitely the film's most enjoyable stretch, and gives Grant the most to do. It's also the section of the film of the most obvious interest to Hawks, who naturally gravitates to material that deals with sex roles and reversals. It's perhaps for this reason that the film wakes up a bit the deeper it gets into this subject, overcoming the sleepy pall hanging over the first two-thirds or so. It still never quite approaches the energetic rhythm of the best classic screwball comedies, but in its relatively laidback, laconic sense of humor it at least has a little more spark and fizz. Even so, as enjoyable as the denouement is, the film as a whole remains disappointing, its promise in theory much greater than the result.