The opening minutes of Jacques Rivette's Love on the Ground are as direct an invitation to his audience as this great director has ever extended: a group of people are silently led by a pair of guides to a humble apartment, where the crowd discreetly lingers to the side and observes a trite melodrama in which a man attempts to juggle his two lovers, who have accidentally shown up at his apartment at the same moment. The man and the two women ignore the intruders lurking nearby, these silent watchers, seemingly unseen, tucked into the corners of Rivette's frame. It is as though the director has invited the film's audience into the fabric of the film itself, to silently observe from an intimate perspective. It soon becomes clear, however, that the audience within the film is actually watching a play, performed in an apartment, and as the play progresses the silent, solemn atmosphere begins to break down: the actors forget their lines and improvise humorous bits of business or clever dialogue, and the audience reacts with appreciative laughter. The appearance of real life being observed with documentary-like objectivity is shattered, and in its place is playfulness, spontaneity, wit.

This interaction of multiple levels of reality — theater, film, audience, actors, "real life" — is typical of Rivette, and he achieves a very potent, playful expression of these key themes in Love on the Ground. The three actors in the opening scene are Emily (Jane Birkin), Charlotte (Geraldine Chaplin) and Silvano (Facundo Bo), and it turns out that their free-wheeling performance in these opening scenes is as sloppily enthralling for the visiting playwright Roquemaure (Jean-Pierre Kalfon) as it is for the film's audience; the fact that the performers are pilfering from and improvising around one of Roquemaure's plays only intrigues him further. He invites the trio to come live at his palatial home for the next week, where they will rehearse a new play he is writing for them, to perform there within a week's time. They agree, and the rest of the film becomes a complex Rivettian game in which reality, theater and film are continually intersecting and weaving together in confounding ways. The actors find themselves playing parts in a drama that they soon learn was modeled off the real history between Roquemaure, his friend the magician Paul (André Dussollier) and Béatrice, the mysterious woman they both loved, and whose disappearance shattered them both.

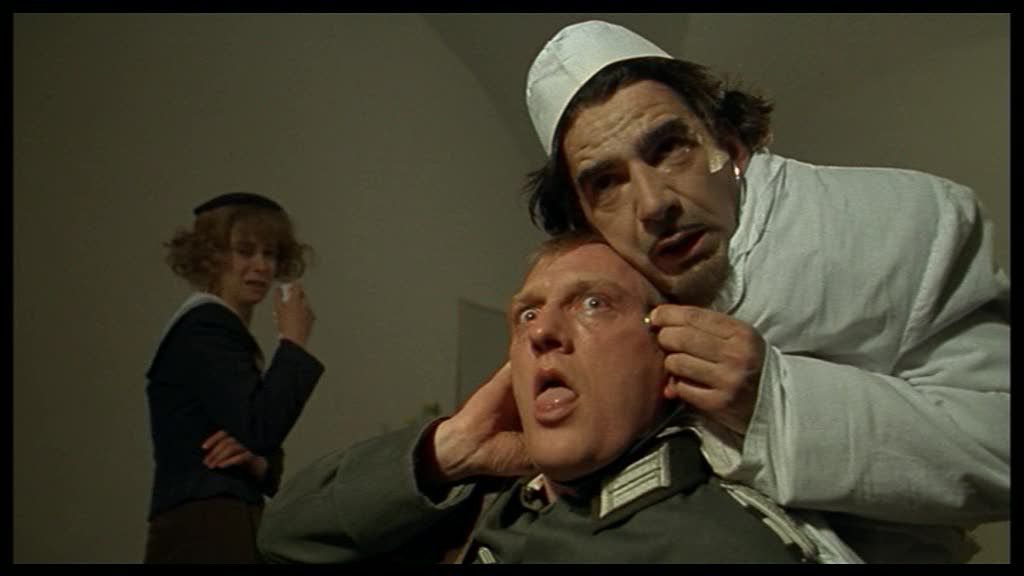

It quickly becomes apparent that Roquemaure is staging this play as a cathartic reenactment of what happened between the trio, with the real events very thinly disguised by false names. Charlotte plays Barbara, an obvious stand-in for Béatrice, even as she becomes Roquemaure's actual lover as well, while Emily, playing a male character named Pierre, goes to bed with Paul, on whom her character is based. It's like sleeping with herself. Only Silvano, playing the playwright's stand-in, largely stays out of these sexual entanglements; he's only there for the money. The confusion of names and alternate identities and artistic identities is complicated further when, in the film's second half, both sexual liaisons and roles prove to be fluid: Emily briefly takes over the role of Barbara, even as Charlotte is becoming ever closer to the real Béatrice by allowing herself to be seduced by Paul. Even the mannered, Igor-esque manservant Virgil (Laszlo Szabo), who would have fit in nicely on the fringes of a Universal horror film, engages in manic, playful seductions of both women.

Rivette thrives in this kind of chaos, using the film's complex layers of reality as a pretext to stage one clever, fun sequence after another. The actors often seem to be improvising, something Rivette heartily encouraged, and many of the film's best moments have an energetic spontaneity that simply seems to burst forth from the performers. Chaplin and Birkin are phenomenal throughout, and each of them is given their best spotlight in independent scenes of drunken revelry: Charlotte attempts to makeout with a Cupid statue, while Emily threatens and teases the harried Virgil, angrily popping an egg in her fist at the scene's climax. The two women are descendants of Rivette's most iconic female duo, the eponymous heroines of Celine and Julie Go Boating, and Love on the Ground is in some ways a sequel to the earlier film. Just as Celine and Julie became involved with an occult mystery, Charlotte and Emily explore Roquemaure's mostly empty mansion like a pair of impish Nancy Drews, creeping through its abandoned rooms in order to discover its mysteries. These mysteries are both magical and horrific: the former because Paul seems to have an uncontrollable ability to trigger lifelike visions for the women he encounters, the latter because the women are half-convinced that Roquemaure is a kind of Bluebeard who actually murdered the mysteriously missing Béatrice, whose room is so lovingly preserved behind a locked door. They both wonder if the ghost of Béatrice is haunting their production of a play based on the missing woman.

The film's magical and supernatural elements extend to its obsession with doubling and mirroring, an obsession that begins with the convoluted assignation of names and roles and replacements in Roquemaure's play, but hardly ends there. Charlotte continually sees herself doubled when she is around Paul, his presence seeming to trigger hallucinatory visions of herself as though reflected in a mirror. Charlotte and Emily also both encounter separate characters played by the same actress, Eva Roelens, who relates to each woman a different tale of woe, about being betrayed by a man, of course. Rivette, always sympathetic to his female characters, makes this film's dominant subject the ways in which women can break free of and subvert the controlling tendencies of men. Charlotte and Emily have free reign here; together, they are not only the narrative's center, but they even get the upper hand in the end.

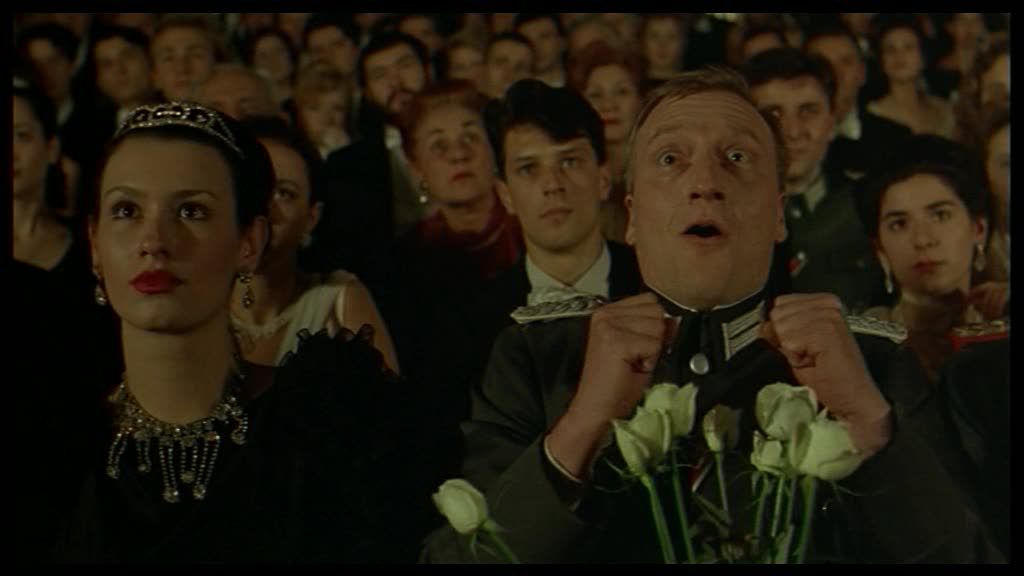

One of the reasons that Rivette's characters, and especially his female characters, often feel so vibrant and free is that they are usually unconstrained by the limits of strict plotting. In this film, the plot is treated as a loose and open-ended framework in which the characters (and the actors playing them — and the actors playing the actors!) can interact, form temporary alliances and relationships, improvise, play, have fun. Roquemaure's play has no set ending, and nobody has any idea of what will happen in its unwritten fourth act until the night of the first performance; the same can be said of Rivette's film. The final half hour is dedicated to the performance itself, and the film's audience gets to find out what will happen at the same time as the audience that Roquemaure assembles at his home for the play. And of course this finale represents the ultimate spillover between the film's multiple levels of reality, in which the real dramas involving Roquemaure, Paul and Béatrice (and the actors as well) intrude upon the performance. The play and its aftermath becomes a struggle to take control of reality, to stage life itself as a grand piece of theater, to write one's own ending, happy or otherwise. This has always been Rivette's agenda, to blend film, theater and life itself into one big messy, ecstatic stew, bubbling over with emotions, both performed and deeply felt.