Diary of a Lost Girl, the second of Georg Wilhelm Pabst's productive collaborations with Louise Brooks, is a potent and gorgeously stylized depiction of an innocent young woman's destruction at the hands of the not-so-innocent. Brooks plays Thymian, a beautiful and sheltered pharmacist's daughter whose dawning realization about the cruel ways of the world coincides with the loss of the security of her family. The opening of the film enacts a lurid symbolic struggle between innocence and sin, naïveté and knowledge. Brooks' Thymian, dressed all in white on the occasion of her confirmation, her eyes wide beneath the iconic ridge of her dark bangs, looks around her with a complete lack of guile, sweetly accepting presents from family and friends, glowing with courtesy and grace.

She seems entirely unaware of all the sexually charged glances being exchanged all around her: the exaggerated leer of her father's assistant Meinert (Fritz Rasp) who all but licks his lips and bulges his eyes like a cartoon wolf when he looks at her; her father's (Josef Rovensky) sexual liaisons with one maid after another; her aunt's (Vera Pawlowa) grim knowledge of these constant affairs; the knowing glances and raised eyebrows of the party guests when they see the new maid Meta (Franziska Kinz), who brazenly stares at her employer with an invitingly wicked smile that openly suggests that the cycle is going to start again. Everyone but Thymian seems to know exactly what's going on, but she is blissfully unaware of the sexual drama surrounding her.

In her pure white confirmation dress, a band of flowers wrapped around her head, she's a vision of innocence so pure and unstained that the mere realization that sin and sexual predation exist in her household produces a fainting spell, confining her to bed as though she's taken ill. She sees the corpse of her beloved maid — who'd committed suicide after being abandoned by Thymian's father — then runs up the stairs in a daze, sees her father with his arm already around the new maid, both of them staring at the camera in a frozen pose, a sly smile on the face of the new maid in contrast to the serene blankness of the dead girl downstairs, and in one fluid motion Thymian swoons to the floor, overcome by the taint of impurity infiltrating her home.

This is only the beginning of Thymian's suffering, as Meinert takes advantage of her vulnerability and rapes her. Pabst freezes the frame at the moment when the creepy druggist lowers Thymian's limp form into bed, and then immediately cuts to a baby carriage being taken out of Thymian's room, months later, carrying the fruit of that forceful union. Thymian's family casts her out, and she's sent to a reformatory, which she soon escapes with her friend Erika (Edith Meinhard), only to fall into a life of prostitution. The man she believes is going to save her, the disgraced and disinherited Count Osdorff (André Roanne), is actually a lazy and pathetic outcast who settles easily into a life of comfort at the brothel with Thymian and Erika. Pabst, though, doesn't portray the brothel as an entirely unpleasant life; the girls have fun and like each other, and Thymian certainly seems happier and better off there than she was under the care of the strict Christian moralists at the reformatory.

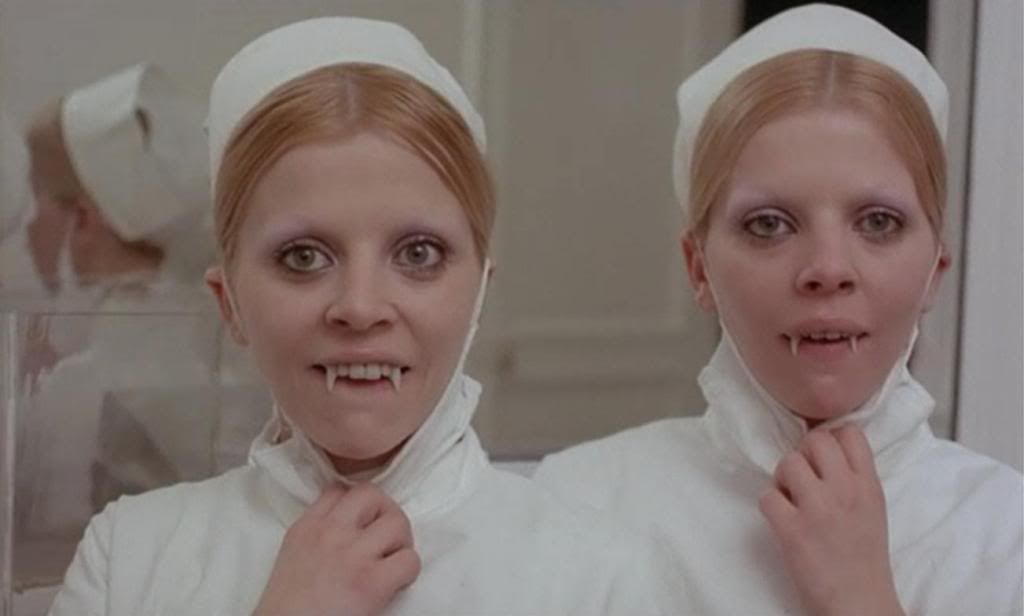

The reformatory is run by a stern mistress (Valeska Gert) whose usually stony face betrays an expression of ecstatic joy when whipping the girls through a frenzied gymnastics routine, and a bald-headed, looming movie monster giant (Andrews Engelmann) who first pops comically into the frame by standing up in front of a sign listing the many things that are "verboten" in this dismal place. This cartoonish giant delights in punishing the girls, grabbing them with a clawed hand at the scruff of their neck as though picking up a disobedient puppy, and his leering sadism is both creepy and hysterical — particularly when he runs a confiscated tube of lipstick across his own mouth, grinning impishly, then uses it to write a reminder to punish the girl he'd taken it from, a note signed with a heart to indicate his sadistic love of punishment.

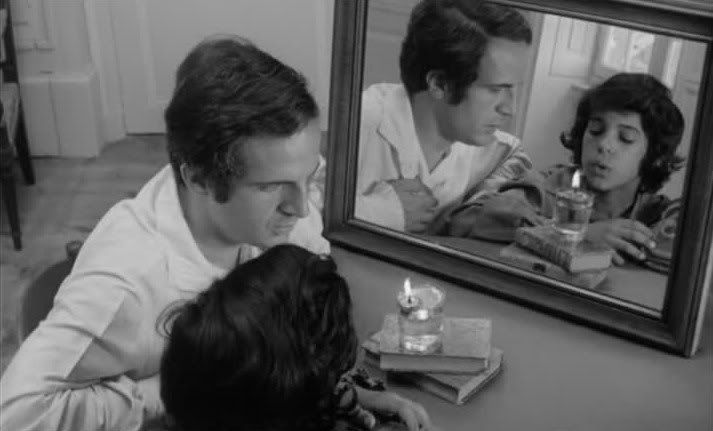

Lesbian eroticism is another obvious subtext here, especially in the reformatory, where most of the girls have clipped, close-cropped boyish haircuts, and Erika introduces herself to Thymian by surreptitiously touching the new girl's leg with her foot and winking at her, echoing Meinert's leering winks. At bedtime, as Pabst pans down the line of girls getting ready for bed, two girls sit in the same bunk, giggling, and fall back into bed together. The scene where the matron tries to seize Thymian's diary is also loaded with suggestive intimacy, with the stern woman grabbing at Erika's bare legs, looking up at the two girls sitting in the top bunk, grasping at them with clawed hands. Later, when Thymian visits Erika at the brothel where she's staying, Pabst emphasizes the brothel's madame putting an intimate hand on the bare back of one of her girls — the gesture is repeated when the madame pushes Thymian together with a male client to dance — and then has Erika kneel before Thymian, taking off her shoes and undressing her, unbuttoning her demure reformatory blouse with its high collar to expose a V of flesh at her neck.

The film is steeped in this kind of sexual suggestiveness. Thymian's downfall has everything to do with sex and money, and sex and money come to be linked in very intimate ways for her. After her first night at the brothel, after she's spent the night with a man — swooning in his arms so that her limp form very much recalls her unconsciousness during Meinert's exploitation of her — the madame hands her an envelope of cash and makes it clear that it's from the man. Only then does the very naïve Thymian realize what's happened, and she recoils from the cash, which Pabst nevertheless emphasizes in a closeup. Much later, when her father dies and she receives an inheritance from Meinert for buying out the pharmacy, the camera glances from the pile of cash to Meinert's smug, cartoonishly grinning face, making it seem as though this too is a transaction, a belated payment for that long ago night when he'd taken her to bed.

It's not all grim tragedy here, though, and there's some limited comedy relief along the way. Among the humorous scenes is a very strange sequence where a goofy guy with a billy-goat beard (a possible anti-Semitic caricature) comes to see Thymian for "dance lessons," and she leads him in a bizarre calisthenic workout inspired by her reformatory exercise drills, while holding a drum protectively/suggestively over her crotch and beating it with a mallet in the way the reformatory mistress had done. The sexual symbolism is especially naked here, but those undercurrents are everywhere in this film.

The plot unravels a bit towards the end with a predictable tonal shift towards an optimistic, redemptive conclusion, seemingly foisted upon Pabst by censors eager to end on a positive note after all this barely coded sex. Even here, though, Pabst's emotional poetry shines through. The film is never less than beautiful, its style fluid and expressionist while also remaining grounded in social realism. And Brooks is just magnificent, with a beautiful and vibrant face that was perfectly suited to the silent cinema. When she smiles, the screen glows, and when she's suffering her eyes seem to contain unimaginable depths of feeling, often assisted by Pabst's very sympathetic photography of her, as in the stunning shot where she stares out a rain-streaked window, the raindrops on the glass standing in for her tears.