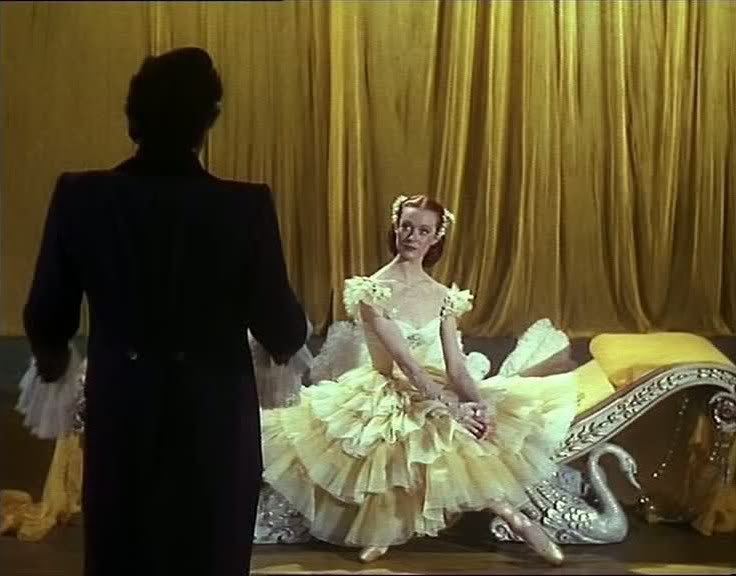

The Black Pirate is a swashbuckling pirate adventure, a showcase for the daring stunts and swordplay of silent action star Douglas Fairbanks. Made in 1926 and directed by Albert Parker, it was one of the first films shot entirely with the two-strip Technicolor process, which makes it one of the rare surviving silents shot in color. Fairbanks plays a nobleman, the sole survivor of a pirate attack that kills his father. He vows revenge on the pirates, though his plan to achieve that revenge is anything but logical, since it consists of joining the pirate band, becoming their leader, and teaching them to be better, more effective pirates, even helping them to hijack a ship while plotting against them.

It never makes much sense, but the silly plot (from a story by Fairbanks himself) provides ample excuse for Fairbanks to show off his exhilarating stuntwork and obvious love of physical feats of daring. He makes a much more convincing pirate than a nobleman, and he seems to enjoy inhabiting this role altogether too much for a man supposedly seeking revenge. To prove his worth to the band of pirates, he hijacks a ship singlehandedly, pulling up alongside it in disguise as a fisherman and swinging around all over the ship, cutting ropes and sails, sending watchmen flying up into the rigging and finally holding the whole crew hostage with a pair of imposing cannons. He does it all with a big, infectious grin on his face, his teeth shining as he leaps and soars through the ship's rigging and swings from one perch to another, clambering around with the agility of a monkey, gliding down the sail with his knife thrust into its fabric or swinging on ropes. Fairbanks always seems to be having a blast when pulling off these stunts, and his enthusiasm is what makes him so fun to watch.

In between the action scenes, the film flounders a bit, and Parker's direction is mostly static and workmanlike. One exception is a great celebratory shot towards the end of the film, after the action-packed battle scene climax — which itself mostly consists of Fairbanks' allies comically jumping on the pirates en masse as if they're playing football — in which Fairbanks is hoisted aloft by his soldiers. He's in the bottom of the ship's hold and is handed up from one set of hands to the next at each level of the ship, the camera tracking up with him while he simply poses heroically, flexing his muscles and grinning proudly, passively letting himself be carried up to the top deck. It's a gloriously silly and self-conscious affirmation of the hero's potency.

Despite Fairbanks' grinning bravado and the flimsy scenario, some grit is provided by making the pirates — with the exception of Fairbanks' one-armed sidekick (Donald Crisp) — credibly sinister. The film is fairly direct about the brutality of the pirates, particularly with regards to their leering intentions towards a princess (Billie Dove) who the crew takes captive. A few of the pirates fight over her and draw straws to see who takes possession of her, just as earlier they'd drawn straws to settle a struggle over a monkey they'd found. The parallel between the two scenes suggests that these bloodthirsty pirates look at women as property, and it's all too obvious what they want to do with this particular piece of property. Of course, Fairbanks protects her from the pirates' lust, and of course the pair falls in love with one another, though it's funny that the princess is visibly relieved, at the end of the film, when she learns that her paramour is not actually a good-hearted pirate but a duke — a potential class crisis averted!

Early on, there's an offhandedly shocking grisly moment in which one of the pirates' captives, trying to keep them from getting a cherished ring, swallows it. But the pirate captain (Anders Randolf) sees this and gestures towards the man. One of the pirates then strolls offscreen with a knife, and moments later wanders back into the frame, the knife and the front of his clothes coated in bright, sticky red, holding out the ring for his captain.

The color is what makes it so startling, and it's one of the best uses of the film's primitive Technicolor. The clunky, unreliable two-strip process results in a restricted palette of mainly reds and blues, sometimes mixed with queasy greens or purples. There's no potential here for subtle color effects, which might be why color film didn't really catch on in a big way until the later three-strip process. Even so, the novelty of a true color silent film, no matter how basic the color scheme, helps to set this film apart as more than the routine pirate adventure it otherwise is.